Lifting

28 May 2025 · 1649 wordsThere are basically three arguments that creatives make against the use of AI in their industries.

First. The argument that AI will replace their jobs, and that’s bad, because then they won’t have jobs. I find this sympathetic in the sense that I do agree that the outcome would be bad for them, and I think this is unfortunate and unfair. No one deserves to go hungry or lose their home because of disruption in their industry. As a society, we can and should do better. But as an argument against using AI to do creative jobs it doesn’t hold water - it’s just Luddite special pleading.

Second. The argument that it is impossible for AI to replace their jobs with anything but a pale imitation, because humans have some capacity that computers don’t, thus AI should not replace creative jobs because doing do would degrade human art. This argument finds support in the real fact that many uses of AI today are the result of corporations replacing pricey human labor with something ultimately not capable of doing the same job. However as a categorical argument it is wholly unconvincing. AI is a tool that in many cases can reduce the labor power required to produce the same product, and in the future (which is what most creatives are really worried about) shows promise of being able to do much more than that.

Third. The argument that making art is good, thus AI should not replace creative work because the result would be fewer people making art.

This argument I fully endorse. I think it’s bad if there are fewer people making art even if the result is that we have more and better art.

However, AI is not the reason that fewer people will be making art. Capitalism is. People are paid a living wage (well, an extremely fortunate subset are paid a living wage) to make art because art is profitable. Many people are required to make art because our tools for doing so (the means of production) are still relatively nascent. But that might change. The labor time required to make a Marvel movie might decrease in the same way the number of farmers required to harvest a corn field decreased.

So to have a problem with people not being able to spend their time on things that are (by their own lights) worthwhile is to have a problem with capitalism. The third argument isn’t about AI per se.

This view suggests a dichotomy between two categories of AI use.

-

AI used as a tool to increase productivity — meaning that less human labor time is required to produce the same commodities.

-

AI used to replace human activity that people themselves find worthwhile.

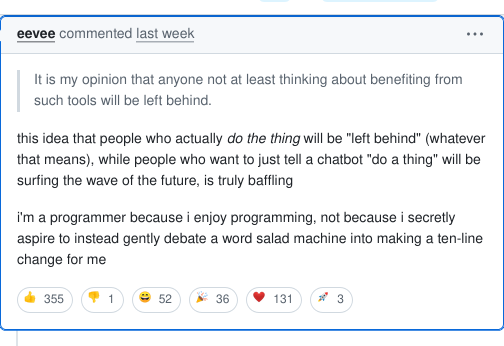

Most debates over AI conflate these two perspectives. For instance, consider this Github comment by eevee:

“I’m a programmer because I enjoy programming” certainly makes rational sense as the perspective of someone with no interest in using AI. Yet the perspective of most programmers as well as every single software company in the world is something very different: “I’m a programmer because it produces a valuable commodity.” Eevee’s comment reflects a failure to consider this view, or more accurately, the two sides are talking entirely past one another.

Take Amazon as an example of what I mean. The New York Times recently reported that programming jobs at Amazon have begun to expect AI use while simultaneously increasing productivity demands on employees. Rather than a creative activity, Amazon programmers are now doing “warehouse work.” You might argue that Amazon is expecting the impossible, and you might be right, but let’s take a long term view here: the reason why so many people work in Amazon’s warehouses for $15/hr is that warehouses are more productive than mom-and-pop stores. If producing code with AI is more efficient than writing it by hand (well, writing it with autocomplete and IntelliSense), businesses that use AI will outcompete those that don’t.

So while I dislike the idea of fewer people spending their time on creative labor (view 3), I disagree with Eevee in that I don’t think the fact that creative activity is inherently valuable means this won’t happen. That’s because under Capitalism the fact that art-making promotes human flourishing does not bear on the reasons we actually make it. All technology, furthermore, disrupts existing ways of life that some find valuable under a Capitalist mode of production. Like Tom Joad, we may appreciate when “folks eat the stuff they raise an’ live in the houses they build,” but modern technology resulted in a world where almost no one lives that way. The fact that homegrown food tastes better, hand-drawn animation looks better, and apps “coded with ❤️” by humans work better doesn’t stem the tide of this change.

Over on Galactic Underworlds, Beatrice Marovich writes about how teaching during a time of rapid AI expansion feels like watching the tide come in. She wonders whether the death of literacy and writing skill could mean a return to a more oral culture — in other words, a shift that has no ultimate moral significance even if it causes her grief. I think this, and not any other, is the perspective from which it makes sense to ask whether we should just give up and use AI tools for anything they’re good at.

After all, as I’ve said, the third argument against AI isn’t really about AI. Capitalism prefers mindless jobs because these jobs produce more and better output than jobs that rely on individuality and creativity. If “warehouse” programming is more efficient, it’s also inevitable. Hobbyists can continue doing what they want in their free time, but like the lost art of raising a roof, creative programming may dwindle in relevance over time.

In the mean time, however, I think a pragmatic stance is suggested: we can evaluate the tradeoffs involved. When it comes to our work, we likely don’t have much choice; whether we’re allowed to refuse AI use at work depends on our employer, and equally directly, on the level of productivity we’re expected to achieve. When we have a choice, however, how are we to decide? Rather than being all-in on AI or rejecting it outright, we can weigh efficiency gains (meaning we can do more things we enjoy) against the extent to which we enjoy the process itself. The solution, in summary: sometimes AI.1

Having presented what I take to be the best argument for a middle ground, I want to square it against the fact that I do not use AI as often as this reasoning would suggest. What’s gone wrong?

Let’s work through an example. Someone told me recently that they pass every email they write through ChatGPT. The justification for this in terms of the argument above is straightforward: writing emails to people is not fun. Neither this person nor I enjoys sitting around worrying about whether we seem nice enough or used an em dash correctly.

Despite this, I was rather horrified. I don’t think I had realized just how much other people were using AI (every other person in the room agreed that they do something similar). For the record, I have never utilized AI in any capacity for anything I’ve written.2 I don’t enjoy writing much more than anyone else, so why not increase my efficiency and finish the process as quickly as I can? I write unassisted because this means doing the work, and doing the work makes me a better writer. I’m going to call this the Lifting principle.

The Lifting principle: increasing the difficulty of a task makes you better at it.

That a type of work is difficult and boring does not mean it is worthless drudgery. Writing benefits you in ways other than by being an inherently enjoyable thing to do. Even if AI replaces literacy with oral culture, this will degrade our capacity to think because we don’t know how to think that way, not because oral culture is inherently better or worse. Ted Chiang’s short story The Truth of Fact, The Truth of Feeling provides an example of a civilization that experiences the reverse, and the effects are just as catastrophic because they happen too quickly for intellectual life to adapt.

Writing presents a form of intellectual exercise that we lack the capacity to replace at present. Speaking personally, I don’t know how to think without writing. I blog, despite rarely hearing from readers (hi!), because it helps me refine my thoughts. I’m a better thinker and even a better person because of this. This is one reason I find the ongoing death of blogs so tragic; they provide one of the few opportunities outside of academia for ordinary people to sit down and seriously think about something. And while education itself at least provides the opportunity, the advent of AI means that fewer students are availing themselves of it. The gym is still full, but everyone is lifting less weight.

Unlike the argument from enjoyment, this view bypasses the efficiency calculus entirely. AI might compensate for making a given task less fun by drastically reducing its duration, but it cannot help you when the inefficiency of the task is the point. When Bertrand Russell imagined a society of leisure in 1932, he indicated that it required much more education than previously common, and credits the leisure class of the past with most of the writing, philosophizing, and reforming. A century later, technology has begun to replace not only labor but leisure as well. We come home from our jobs too tired to lift; the robot will do our exercises for us.

I want more terrible blogs nobody reads in the same way I want more awful music on SoundCloud for nobody to listen to. Creativity contributes to human flourishing not merely as an inherently valuable activity, but as a means by which we improve ourselves.

-

Some people have moral objections against using AI, which is one reason this argument might not go through. There are three basic categories of moral objection: (a) AI use contributes to climate change, (b) AI use constitutes theft of the intellectual property of others, and (c) AI use constitutes plagiarism.

I think the energy use argument against AI is greatly overstated. The argument from intellectual property I take to be completely bogus; as a society we sustain intellectual property because it’s pragmatically useful, not because my authorship of this blog post (for example) morally contaminates your use of ChatGPT to rewrite an email because OpenAI scraped it. Last, plagiarism can be avoided by clearly acknowledging and citing the LLM used to generate any substantive amount of text.

I’m aware that some people disagree with one or more of these claims in good faith, but moral issues with AI are not the point of this post, and I’ve left this in a footnote to try to avoid getting sidetracked. ↩

-

I do have interest in using it as a grammar and style checking tool, but haven’t come across good ways to do this yet. ↩